Epi-Proj

Efficiently computing epigraphical and level set projections for problems in nonsmooth optimization

Given an extended-valued convex function \(f\colon \mathbb{R}^n \to [-\infty,\infty]\) its epigraph is defined by

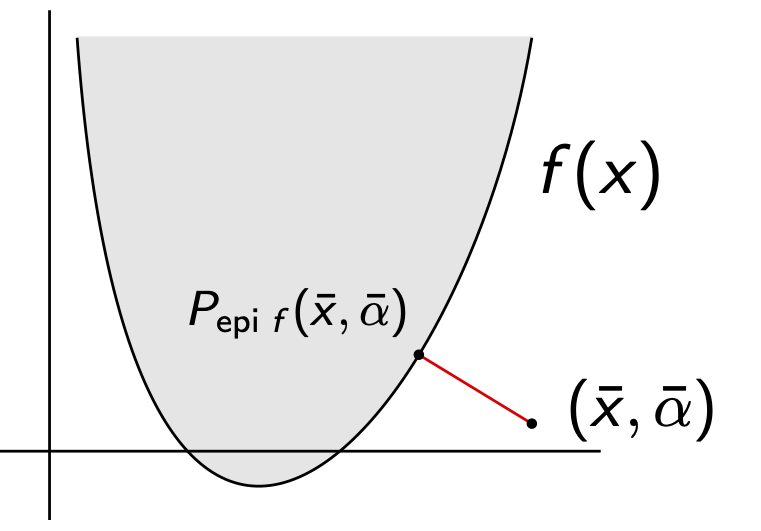

\[\mathrm{epi}(f) = \{(x,\alpha) \in \mathbb{R}^n \times \mathbb{R} \mid f(x) \leq \alpha\}\]Intuitively, the epigraph is the area that lives above the graph of the function. A related concept is that of a level set. Fixing \(\alpha\in \mathbb{R}\), the \(\alpha\) level set for \(f\) is defined by

\[\mathrm{lev}(f,\alpha) = \{x\in \mathbb{R}^n \mid f(x) \leq \alpha \}\]Level sets are quite familiar. For example, given a vector norm \(\| \cdot \|\) on \(\mathbb{R}^n\) the closed ball centred at the origin of radius \(r\) is the \(r\) level set for the norm:

\[B_{r,\|\cdot\|}(0) = \mathrm{lev}(\|\cdot\|, r)\]In particular, many optimization problems with origins in statistical learning [Tibshirani, 1996] and compressed sensing [Donoho, 2006] employ the \(\ell_1\) norm as a regularizer to encourage sparse solutions. These problems can be recast as constrained optimization problems where the constraint is of the form \(\|x\|_1 \leq \delta\). In problems with epigraphical or level set constraints such as this, many optimization algorithms will often need to take their current iterate and find the closest point in the feasible set. This is known as computing the projection onto the corresponding epigraph or level set at each iteration.

Efficiently solving this sub-problem is of interest, and it turns out to yield a fruitful study of the variational analytic properties of the so-called proximal operator [Moreau, 1962]:

\[\mathrm{prox}_f(\bar{x}) := \mathrm{argmin}_{u\in \mathbb{R}^n}\{f(u) + \frac{1}{2}\|u-\bar{x}\|^2\}\]The prox operator is a generalization of the usual Euclidean projection operator, and plays an important role in modern first-order methods for optimization.

Our result shows that the projection onto the epigraph can be computed by solving a differentiable scalar convex optimization problem, and moreover when the objective function has semismooth structure this technique is amenable to superlinear convergence guarantees. More precisely:

Theorem 1 [Friedlander, Goodwin, Hoheisel]: Suppose \(f \colon \mathbb{R}^n \to (-\infty,+\infty]\) is a closed (meaning its epigraph is closed), proper (\(f(x) < \infty\) for some \(x\)), convex function, and \((\bar{x},\bar{\alpha})\in \mathbb{R}^n\times\mathbb{R}\). Then

\[P_{\mathrm{epi}(f)}(\bar{x},\bar{\alpha}) = \begin{cases} \left( P_{\mathrm{cl}(\mathrm{dom} f)}(\bar{x}),\bar{\alpha}\right), & \text{if } f( P_{\mathrm{cl}(\mathrm{dom} f)}(\bar{x})) \leq \bar{\alpha}\\ \left(\mathrm{prox}_{\bar{\lambda}f}(\bar{x}),\bar{\alpha} + \bar{\lambda}\right), &\text{else} \end{cases}\]where \(\bar{\lambda} > 0\) is the unique root of the strictly decreasing function \(0 < \lambda \mapsto f(\mathrm{prox}_{\bar{\lambda}f}(\bar{x}))-\lambda - \bar{\alpha}\).

For level sets, the situation is largely the same except the problem is no longer strongly convex, so the root may not be unique. The analogous formula is

\[P_{\mathrm{lev}(f,\bar{\alpha})}(\bar{x}) = \begin{cases} P_{\mathrm{cl}(\mathrm{dom} f)}(\bar{x}), & \text{if } f( P_{\mathrm{cl}(\mathrm{dom} f)}(\bar{x})) \leq \bar{\alpha}\\ \mathrm{prox}_{\bar{\lambda}f}(\bar{x}), &\text{else} \end{cases}\]where \(\bar{\lambda} > 0\) is any root of the non-increasing function \(0 < \lambda \mapsto f(\mathrm{prox}_{\bar{\lambda}f}(\bar{x})) - \bar{\alpha}\).

The naive approach for finding these roots is to apply bisection, but with some additional structure we can exploit semismoothness to yield more efficient algorithms. You can think of semismoothness as a weaker assumption than differentiability, but still powerful enough to help us. If we define \(g \colon (0,\infty) \to \mathbb{R}\) by \(g(\lambda) = f(\mathrm{prox}_{\bar{\lambda}f}(\bar{x}))\), then knowing whether \(g\) is semismooth is an important step to checking whether our algorithmic framework will apply. Ultimately the semismoothness of \(g\) is intimately related to the semismoothness* (a more recent notion due to [Gfrerer and Outrata, 2021]) of \(\partial f\), the subdifferential of our original function. This requires a more careful treatment of set-valued mappings, but there are some simple conditions under which semismoothness* is easily verified.

If we grant ourselves semismoothness of \(g\), we can employ generalized variants of Newton’s method to find roots of \(g\) in superlinear time. Numerical experiments for the problem of \(\ell_1\) ball projection showcase the effectiveness of our method compared to more specialized algorithms such as [Condat, 2016]. All the details can be found in my recent paper with Tim Hoheisel and Michael P. Friedlander, From Perspective Maps to Epigraphical Projections .